Film Review: Three Thousand Years of Longing & The Good Boss

Fantasy and Reality in Cinema

Three Thousand Years of Longing & The Good Boss

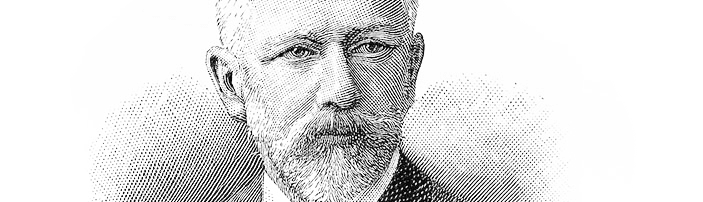

Reviewed by Marc Glassman

The Good Boss (El buen patrón)

Fernando Leon de Aranoa, director & writer & coproducer

Spain, 2021, 120 minutes

Starring: Javier Bardem (Julio Blanco), Manolo Solo (Miralles), Almudena Amor (Liliana), Oscar de la Fuente (Jose), Sonia Almarcha (Adela), Fernando Albizu (Roman)

Three Thousand Years of Longing

George Miller, director & co-script w/Augusta Gore

Story based on “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye,” by A.S. Byatt

Starring: Tilda Swinton (Alithea Binnie), Idris Elba (Djinn), Aamito Lagum (Queen of Sheba), Burcu Golgedar (Zefir), Pia Thunderbolt (Ezgi)

The Good Boss (El buen patrón)

What do you imagine when you hear the word “boss”? Is he (and 99% of the time “he” is the operative term) a strong stern figure, scaring you into doing his will? Or is he sweet-tempered, almost effortlessly persuading you to do more than possible for the common good? Or is he aloof, thinking deep thoughts, while bending his ferocious coldness into your very being? Whatever mood or persona he projects, the boss wants to dominate you so that the “greater good,” the factory, the office, even the government operates more effectively though you and your friends are devastated in the process.

The Good Boss is a cool, cleanly constructed satire on the “patron,” as he is known in Spanish or French, or “chef” in German, or “gaffer” in colloquial British—the “man” as we Zoomers used to say in the Sixties. Whatever personality he has, the boss is likely a charismatic white middle-aged heterosexual man, who takes control in every circumstance and handles every situation, whether with morality or not. If you were casting a film, and looking for a “patron,” who could be better than Javier Bardem, the brilliant Spanish actor who won an Oscar for playing a cold-blooded serial killer in the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men but has also played other kinds of complex roles such as the gay poet Reinaldo Arenas in Before Night Falls?

Bardem plays Julio Blanco (his last name meaning “white “in Spanish), the owner of a factory, which makes scales, good for weighing meat or, metaphorically, measuring justice. As the film begins, Bardem’s Senor Blanco is exhorting his employees in the scales factory to produce not only their best efforts but to do so with love in their hearts. He’s giving the speech because the company is up for a huge regional reward as the best factory in the district, which will give Blanco more prestige and money. Blanco’s mantra is that the factory workers are his family and they are all working together to make the best product while enjoying his almost suffocating but ostensibly charming presence.

Almost instantly, there is trouble in paradise. While Blanco is making his familial speech, Jose, an accountant, is being fired for being “redundant,” and he’s very angry over his dismissal. Without realizing It, Blanco has created his greatest nemesis. Jose sets up camp across the street from the factory’s entrance, shouting slogans, making banners and eventually attracting media attention for his efforts, which morph from him wanting to get back his job to an overwhelming desire to expose Blanco as a brutal boss, not the kindly “patron” he purports to be.

Blanco’s problems increase as his one of his senior employees, Miralles, makes mistake after mistake, most of which are covered up by a stellar worker, Khaled, who we quickly realize, will never rise far in the factory because of his race and religion. Miralles, which means mirror in Spanish, is a second-generation employee of the factory—his dad worked closely with Blanco’s father—and he’s known the “patron” all his life. Blanco seems to genuinely want to help Miralles, but his solution, which is to get him drunk and then invite two young and lovely factory interns to join them, backfires ignominiously. Miralles insults his “date” while Blanco, not for the first time, has an absolutely satisfying encounter with a young employee—in this case, Liliana, a beauty who is clearly fixated on him.

We soon find out that Blanco has not recognized that Liliana is the daughter of one of his old family friends, who had moved away many years ago. The film could have been thrust into a bedroom farce at that point, but the Spanish auteur, director-writer Fernando Leon de Aranoa, wisely moved the story away from that over-wrought premise.

Instead, the film moves into a confrontation between Blanco and Jose, whose anger and slogans are matching that of radicals in Spanish and Latin American history. Blanco transforms from a fallible capitalist chasing after an award into a brute and a Fascist. The comedy becomes a tragedy—for a while, only to morph again through a darkly comic conclusion.

The Good Boss is a fine satirical comedy, and how often do you get to see that? Perhaps it’s too exemplary; if you know this genre, you can see de Aranoa manipulating situations so that didactic points can be made. However, Bardem’s performance is exemplary: he moves his character from a figure of fun to a terrifying oligarch. He is so dominant and entertaining that the film can’t help but remain interesting. Funny, moving and perhaps a bit more, The Good Boss is well worth seeing.

Three Thousand Years of Longing

Making a movie about storytelling is risky business. You’re immediately immersed in the basic questions of what makes wonderful tales, why audiences are attracted to them, and how people are seduced into accepting their often-outrageous premises. Interesting queries, of course, but they provoke the opposite of what films usually try to do, which is to lure you into a fantastic world that will play with your emotions—and not necessarily your intellect—for a couple of hours. Even wonderful contemporary writers like the British feminists Marina Warner and the late great Angela Carter found it hard to strike a balance between entertaining people with mythical tales and analyzing them. But that’s the task, which George Miller set out to do with his fairy tale film, Three Thousand Years of Longing.

Miller, who is most famous for his post-Apocalyptic action-filled Mad Max films, has definitely proven his ability to visualize and dramatize crazily imaginative scenes and stories. His 2015 feature Mad Max: Fury Road is an absolute stunner of a film, with brilliant shots and no-holds-barred sequences from end to end. But her he holds back, letting the literary conceit of another brilliant British woman writer, A.S. Byatt, relate the story of Alithea Binnie (Tilda Swinton), an academic, a narratologist, who unleashes a Djinn (Idris Elba) from a bottle and is forced to deal with the consequences.

Three Thousand Years of Longing feels quite literary although Miller effortlessly uses special effects when the Djinn actually gets to perform magic. Yet the film is inherently literary or theatrical as its structure is based on a covering tale, which is returned to after the four other stories are told. In the lead tale, Swinton’s Alithea unleashes Elba’s Djinn, who tells her how he has ended up with her, in a Turkish hotel room during a university conference.

Two of the Djinn’s tales are worth evoking, in my estimation, while the others are disappointing. In the first one, the story of Sheba and Solomon’s love affair is rendered gorgeously and it’s delightfully subversive with the black Queen being courted by Solomon, not the opposite, as purported in Christian and Jewish liturgy. The next two, about a slave girl who would rather die than give up her fantasy of a prince and two doomed brothers, one a warrior and the other a hedonist, don’t really seem worthy of screen time.

But that’s not the case of the Djinn’s final tale about a Sultan’s bride, whose passionate desire is to pursue knowledge. The Djinn gives her the wish and acts as a mentor as she learns about everything from mathematics to astronomy. The love affair between the Djinn and the wife is the most exciting of all of the stories as it’s predicated on a love of learning and an idealistic hope for a better world. When it goes wrong, one wonders: can the Djinn’s wishes ever come true?

The majority of the film—two-thirds is my estimate—takes place before Miller’s brilliant leads Swinton and Elba get to play out a personal drama. After some dithering, Swinton’s quiet academic decides to make her wish be that the Djinn fall in love with her. It’s their relationship, which forms the narrative for the final sequences in the film, and it’s very well done. The story, at last based on Byatt’s work, is about a narratologist, who is in love with a Djinn, who may or may not exist. The love affair between two points of view about stories—one mystical and the other scholarly—forms the philosophy of Miller’s film. Are we persuaded by either POVs? I don’t think so.

Three Thousand Years of Longing is a well made film. I wish I could endorse George Miller’s movie wholeheartedly, but I can’t. I’m disappointed. This film suffers from what the great Palestinian writer Edward Said called “Orientalism.” Miller’s version of “Arabian Nights” may seem positive but its depiction of the Ottoman Empire is transparently false. Then, there’s the often-naked Black actor Elba being the object of fetishization by women of Arab and Caucasian descent. Is that OK? I felt queasy watching some scenes.

I know it’s a lot to ask but I wanted magic in this meta-film about narratives. That it didn’t happen is sad for all of us. I applaud the ambition of the film. It doesn’t succeed but at least Miller’s creative team has made Three Thousand Years of Longing into a work that intermittently comes to a life. And when that happens, magic appears.